Last week, I published the first in a series of articles on how COVID-19 and the associated economic and social crises have impacted the trajectories of several “disruptors” in the transportation ecosystem. The first installation was all about ride-hailing, and this week I’ll dive into the closely related topic: connected and automated vehicles.

On a cold, dark night in Berlin, I took my first ride on an AV shuttle, a test Olli by LocalMotors.

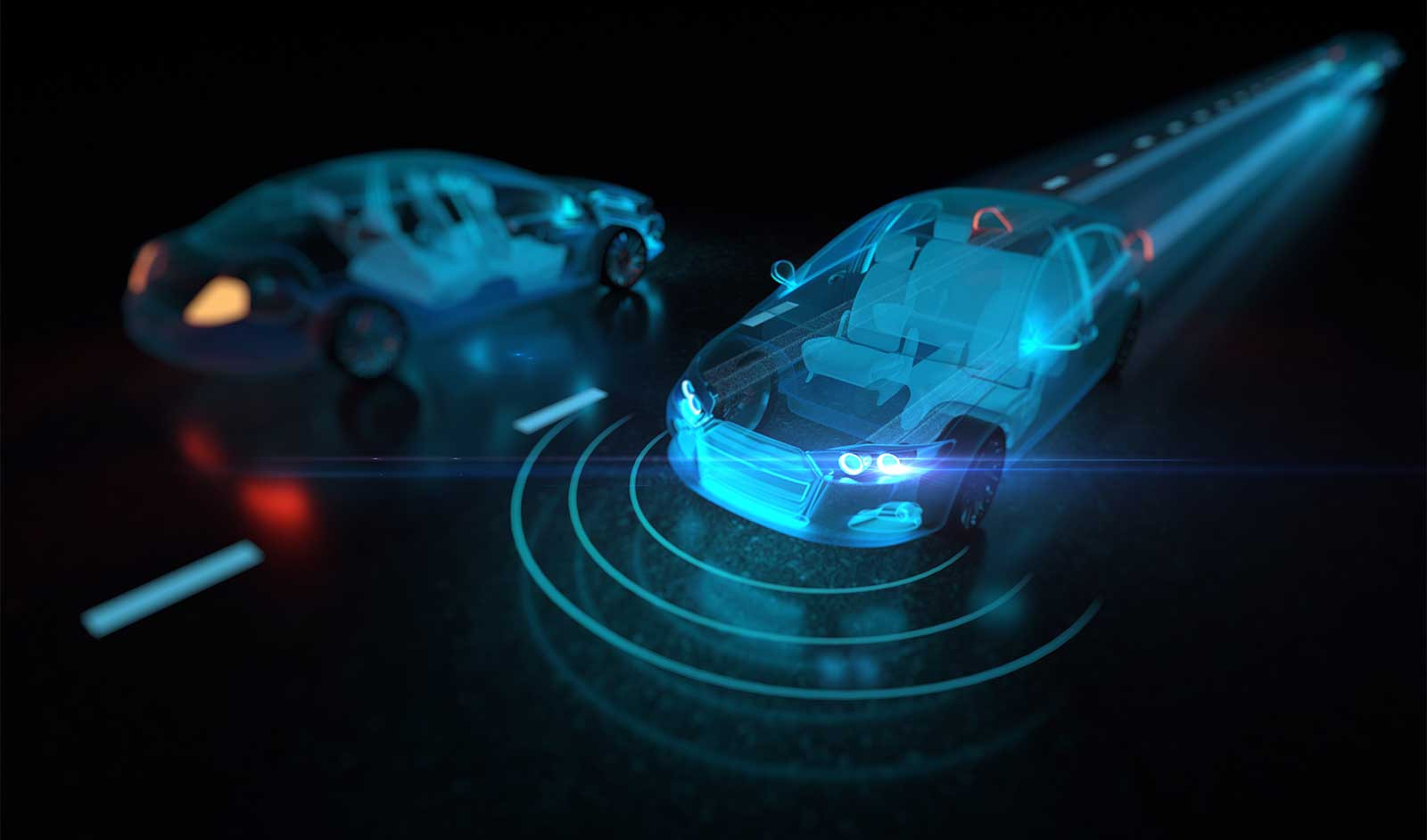

Automated, or self-driving, vehicles (AVs) took a bit of a roller-coaster ride pre-COVID. Hype and expectations peaked around 2017, with predictions running rampant over how quickly each manufacturer could produce fully automated vehicles. A series of high-profile crashes brought some of those hopes closer to reality, as technology companies and car makers became more realistic about the challenges in front of them. But despite changes in rhetoric, AVs remain a major priority for every vehicle manufacturer, from passengers cars to buses to trucks. Automated Driver Assistance features on cars have continued to improve, as lane changing, lane keeping, and emergency braking systems improve safety on the roads. These are incremental steps on the road to full autonomy, and the pandemic has not slowed this progression.

It seems as though the pandemic may ultimately increase the demand for AVs from several different directions, including:

Robo-taxis: The pandemic strengthens the potential for successful robo-taxi business models, by providing a relatively ow-cost, socially-distant travel option for those who don’t own a car. Robo-taxis are being pursued by Uber and Lyft and more traditional vehicle manufacturers like Ford, all of whom see ride-hailing or Mobility-as-a-Service as a key part of the mobility ecosystem of cities in the future. Of course, as many of these companies face economic difficulties and downsizing, their ability to invest in innovative R&D will be more limited, potentially slowing the technology development somewhat.

Trucks: The Great Toilet Paper Shortage taught us all about the importance of supply chain redundancy. Automation could help provide some of that redundancy by ensuring that freight trucks could keep running even in the face of a health crisis and any ensuing labor shortage.

Delivery Vehicles: The phrase of 2020 may be, “contactless delivery”, for its role in keeping millions of people fed, stocked, and employed throughout this pandemic. As we get used to our pizza being left on the front porch instead of handed to us, we may be easing ourselves into a future in which deliveries are made by automated robots, further limiting contact.

Private Cars: As many continue to telework, some people have been questioning why they need to live so close to their office. So far, there has only been limited evidence of people leaving their cities to find larger, more socially-distant homes in the suburbs and exurbs. However, as the pandemic stretches out, these trends seem to be strengthening – evidenced by significant drops in rent prices in major cities across the country (led by a 31% drop in San Francisco). Should people chose to stay in these less urban areas once the emergency passes, they would need to drive more and further to reach essential places, and may make them more interested in purchasing an AV to make those drives less onerous.

Connected Vehicle (CV) technology, which allows vehicles to communicate with the world around them, is often thought of in the same breath as vehicle automation, but is really a separate set of complementary technologies being developed independently. But the biggest disruption for CV technology isn’t caused by the pandemic at all, but instead related the potential proposed FCC regulatory change that would may reallocate the “safety spectrum” previously reserved for Dedicated Short-Range Communications (DSRC) to other uses. If the change moves forward, it will shape the future of CV technology moving forward by requiring the use of different communications technologies and changing deployment strategies for infrastructure owners and vehicle manufacturers. The experts are fighting this battle at the Federal level – planners like me are watching to see what the impacts will be.

Again, we have a number of uncertain trends to watch here, related to the potential markets for AVs. Some of these are only likely to spur demand if the pandemic continues to linger into the long-term. But it is perhaps the pandemic’s impacts to the economy that will determine the trajectory of connected and automated vehicle technologies moving forward. A weak economy will likely have a number of negative impacts: high unemployment limiting people’s ability to buy new cars with new technologies; budget shortfalls limiting governments’ ability to implement the smart infrastructure necessary for vehicle connectivity; and lower profits also potentially limiting the amount of money available to spend on the R&D required to truly perfect connected and automated vehicles. Not that any of us needed another reason to hope for a fast and strong economic recovery. Share your thoughts in the comments.

Next time we’ll leave cars behind for a little bit and talk about the impacts of the pandemic on micro-mobility. Walking, biking, and even scooting (scootering?) have always been socially distant, and seem custom-made for our new lives of short trips near home. But they don’t work uniformly for everyone – and then of course, there’s winter...