Trucks ensure stores have our favorite foods and make it possible for the new shoes we want to be delivered, often overnight, right to our front door. With e-commerce rising dramatically, communities and the agencies that serve them face increased urgency to better understand and reduce the negative impacts of truck traffic. Our team conducted a study with the Chicago Department of Transportation (CDOT) to do just that. The findings and recommendations, which apply to urban and rural communities nationwide, appear in the February 2025 Southwest Industrial Corridors Transportation Study (SWICTS), which concentrated on the Southwest Side of Chicago.

In this blog, we’ll cover how the study team took an innovative approach to:

Understanding the negative impacts that freight imposes on the City’s local communities and transportation systems while recognizing and supporting the critical role that freight plays in Chicago’s economy.

Developing a framework for addressing the negative impacts of trucks within communities.

Identifying existing and potential strategies that the City and its partners can use to address these negative impacts in the short and long term.

The Negative Impacts of Trucks are Undeniable

Chicago is home to the largest rail/truck intermodal port in the country and the third-largest economy in the United States. Trucks operate at all hours throughout Chicago, bringing goods to stores and restaurants or collecting, delivering, and transferring freight between other modes for a wide array of industries. Despite the benefits of this complex and intricate system, Chicago’s communities are impacted negatively by freight in many ways, including:

Increased traffic congestion during morning commutes. Trucks take up additional space on roadways, causing congestion due to their size and handling characteristics. One SWICTS focus group participant said, “I live on a one-way street in the city, and there typically are two Amazon trucks and a FedEx truck blocking traffic two or three times a day.”

Infrastructure deterioration, such as potholes, on roads that were not designed for heavy truck traffic. The greater size and weight of trucks increase wear and tear on roadways, leading to increased maintenance requirements, state-of-good-repair expenditures in communities, and even creating safety risks.

Conflicts between large trucks and people waiting at bus stops, walking, or riding bikes. High volumes of trucks make people feel unsafe near roadways, which disproportionately affects vulnerable road users. Sometimes, schools or other sensitive uses, such as hospitals, are located near industrial facilities, increasing the exposure of children and vulnerable groups to truck activity.

Noise pollution from engines and decreased air quality from truck emissions. Air pollution from trucks contributes to respiratory issues and is correlated with higher incidences of heart and lung disease, while noise pollution exposes residents to increased stress/anxiety levels, high blood pressure, and heart disease, among others.

Tangible and perceived negative community impacts. Community stakeholders are concerned about trucks taking up too much space on the road, trucks parked illegally in neighborhoods, safety, and limited economic development.

“I live on a one-way street in the city, and there typically are two Amazon trucks and a FedEx truck blocking traffic two or three times a day.”

– SWICTS focus group participant

E-commerce has only exacerbated these issues. Truck volumes in Chicago as of January 2023 were 20 percent higher than pre-pandemic levels, bringing increased complaints from community organizations and advocacy groups and demands that public agencies address public health, safety, and infrastructure concerns.

A Wicked Problem

Because trucks are so critical to moving goods in the current economic system, there is no easy remedy for solving the challenges associated with trucks. The idea of removing trucks from communities via a quick fix—such as through punitive regulation—may seem attractive at first glance. However, experience has shown that this type of unilateral action often leads to immediate and substantial negative economic and social impacts, both to the detriment of the region and the community.

The complexity of the issues surrounding trucks, including balancing the tradeoffs between various potential solutions, can be described as a “wicked problem,” one in which there is no clear or attainable solution that overcomes the economic and social influences that create it.

One example that illustrates the challenge of addressing this wicked problem is the circular pattern of increased truck traffic from economic development efforts in neighborhoods.

If you want to read a full, in-depth discussion of the tradeoffs public agencies must contend with when addressing the adverse impacts of trucks, read the full study report here.

The Circular Pattern of Truck Traffic and Economic Development in Neighborhoods

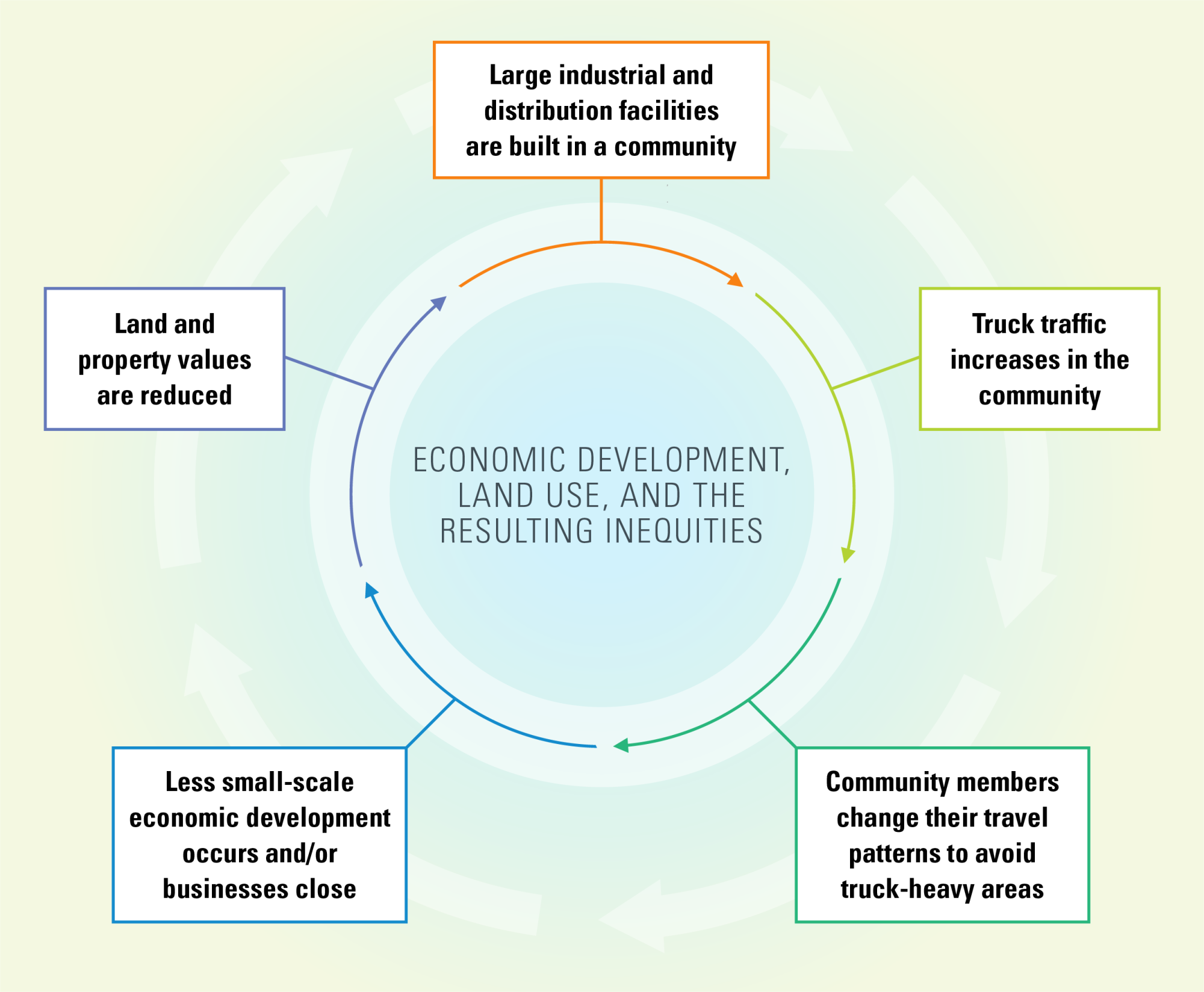

We found that the pattern of economic development, land use, and the resulting inequities in surrounding neighborhoods are circular or self-reinforcing. This finding helped Chicago agencies frame the scale and scope of action needed to make meaningful change within communities. The pattern works like this...

The pattern of economic development, land use, and the resulting inequities in surrounding neighborhoods are circular or self-reinforcing.

Developers and warehouse operators in the e-commerce era want close proximity to neighborhoods to reduce delivery times. Higher-income neighborhoods have more expensive land costs that make warehouse development less cost effective. They also have more political capital to resist the construction of those warehouses.

As a result, developers seek lower-cost sites, and often these sites are in low-income neighborhoods—areas that are more likely to have industrial development, wider, higher-capacity streets with higher speed limits, and decreased foot traffic due to safety risks.

These factors ultimately limit neighborhood-scaled businesses. The lack of a robust local economy contributes to lower property values, which creates a more favorable market for the industrial and warehousing sectors, who are looking to build in areas with low real estate costs.

Understanding this cycle is critical to both issue analysis and solution development, as the self-reinforcing pattern shows the interrelationships between these issues as well as the need for a multi-vector solution.

Navigating Regulatory Challenges: When Objectives Don’t Align

Regulatory strategies are perhaps the most common tools at the hands of public agencies to deal with the impacts of truck traffic, as they utilize regulatory powers directly granted to an agency to address impacts. Regulatory action can result in either mitigation or transformative effects. But freight issues are regulated by a complex framework of local, state, and federal agencies with a wide array of functions. Each branch of government administers specific functions based on its jurisdictional authority. While they may work together on shared goals, each level of government has its own objectives that don’t always align.

Consider the example of air quality regulation in a city like Chicago. Regulations regarding permissible air pollution levels are set at the federal level through acts of Congress (legislative) and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rulemaking (executive), and the U.S. EPA monitors regional air conditions at the state level to ensure compliance (executive). At the local level, the Chicago Department of Public Health inspects facilities, issues permits, and enforces local laws (executive), while the City Council sets zoning and land use regulations that determine what uses are permitted within the City limits (legislative). Across all levels, polluters that violate standards can be fined by law enforcement agencies or tried in criminal and civil courts (judicial).

With these multiple actors comes a higher risk of uncertainty. Political change and policymaking at each level of government create the potential for dramatic changes in the regulatory environment that can complicate long-range planning at the local level.

A Framework for Action

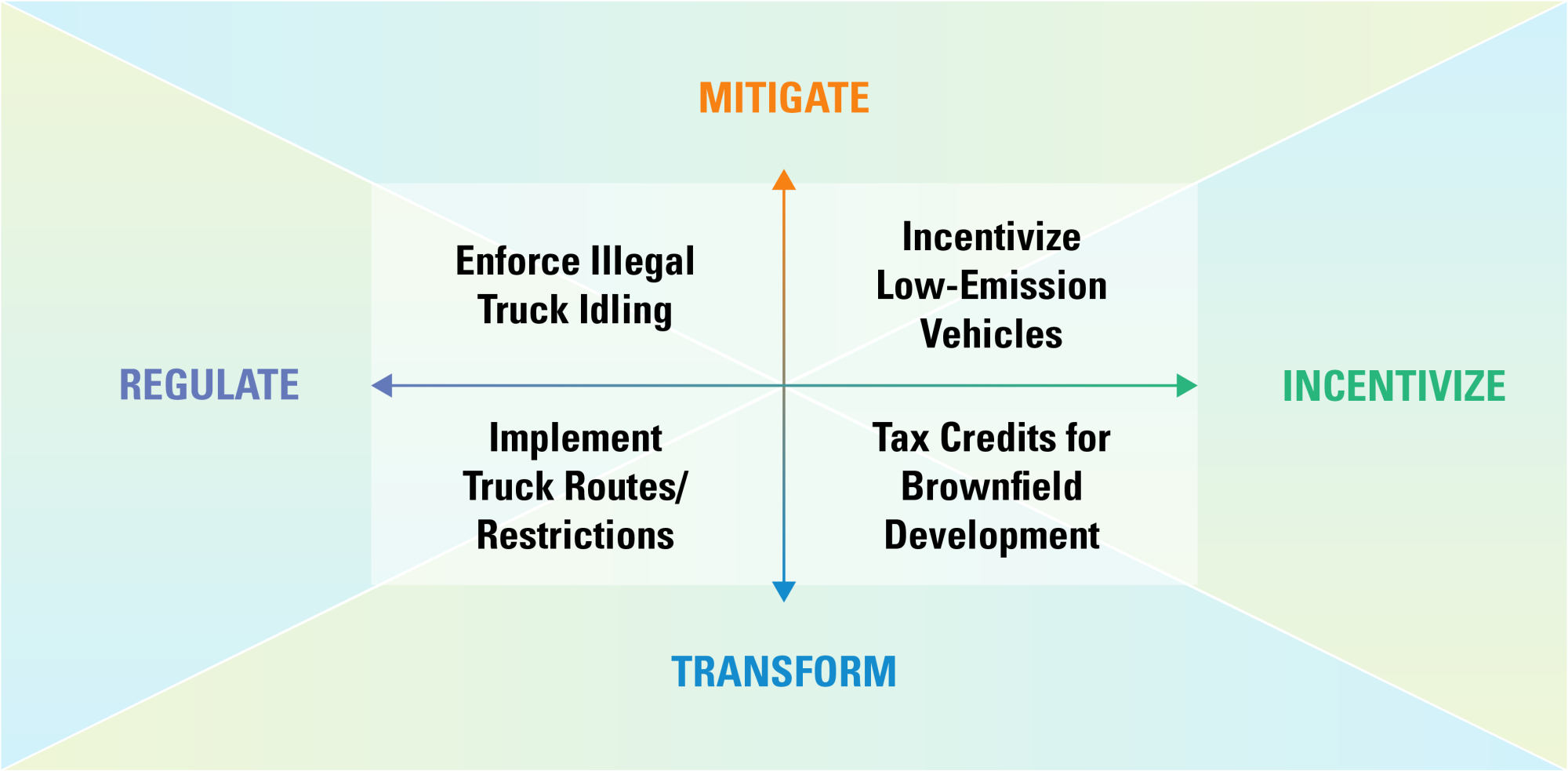

Since a wicked problem cannot be addressed by a single solution, we built a conceptual framework that helps agencies organize choices for building a multipronged approach, understand the menu of solutions available to them, and assess the tradeoffs. The two-axis classification framework allows governments and policymakers to categorize different strategies and determine how changes may be designed and implemented.

The two-axis classification framework shows examples of opportunities that fall under each quadrant.

The two-axis framework we created for the SWICTS shows one axis as a spectrum between mitigation, which reduces the impact of a negative externality, and transformation, which removes or changes the source of the externality. Mitigation does not change the cause of the externality but may be less resource-intensive to implement. Transformation may eliminate the underlying risk but may be costly and complex to implement.

The other axis shows a spectrum between regulatory powers and incentives. Regulatory powers set rules and requirements that businesses or other stakeholders must follow in order to engage in a particular activity. Incentives rely on market forces to encourage actors to adopt certain behaviors in response to changes in costs or benefits associated with those behaviors. Market forces may not result in the desired behaviors, but regulatory powers may require extensive administration costs to produce the preferred outcomes.

A multipronged approach like this can be seen in other areas, like safety. Along state highways, strategies like flashing lights, electronic messages, and the use of state highway patrols to ticket drivers for rule violations are designed to influence drivers to change their behavior voluntarily, representing a Mitigation/Incentive approach. Voluntary behavioral changes can also be reinforced by the infrastructure of the roadway, like barriers to separate directional traffic and rumble strips to alert drivers when they are departing from the roadway, which represents a Regulate/Transform approach. They are designed to complement each other, filling gaps to improve safety through multiple vectors.

We used this framework to facilitate discussions with CDOT and its partner agencies, including the CDPH and the Chicago Department of Planning and Development (CDPD). The framework helped the agencies understand the field of solutions and the relationships between these solutions, enabling them to consider the best ways to engage stakeholders and distribute resources.

What Can You Do?

While there are challenges to reducing the negative impacts of truck parking in your community, the SWICTS revealed three key actions communities can take to start making improvements.

Understand your regulatory framework. Creating sustainable change requires not only developing solutions but also knowing which agencies need to be involved to implement the change. In the SWICTS, we developed a table that outlined the agencies involved in reducing negative truck impacts. This helped to identify the authority of each agency and the important role they could play. The table included agency roles, responsibilities, and authority. This helped to give a big picture view of which agency to work with on specific projects.

Identify innovative data sources and share data between public agencies. Consider using innovative data sources such as emissions collectors. This low-cost option provides valuable information without spending a lot of money. Also, work together to identify data sets that are already being collected at partner agencies. The SWICTS recommendations included developing a cross-agency data sharing agreement so that key transportation, health, and land use metrics could be used to support decision-making across agencies that together could help to reduce negative impacts.

Work with your community and stakeholders. Identify the federal, state, and local needs in the community by engaging stakeholders. One solution in the SWICTS involves the enhancement of the local 311 information system to include an option for truck-related complaints. This recommendation grew out of a robust stakeholder engagement effort, including a series of structured listening sessions that revealed there was no direct contact for the community to identify concerns.

Connect with Us

Are you interested in learning more about how the SWICTS could inform your efforts? We have a deep bench of freight planning, economic impact analysis, and air quality experts. Our planning expertise leverages freight management strategies, public health assessment tools, cost-effectiveness analyses, and project evaluation and monitoring to help agencies identify, prioritize, and evaluate effective freight impact reduction strategies and improve community health and well-being.