Before the safety community began collecting and analyzing crash information in a systematic way, safety campaigns were planned on hunches, biases, personal preferences, and “the way it was always done.” Arguably, we couldn’t even be sure what the real problems were. Today, we can look to the work of this dedicated community to know the who, what, where, when, and why on traffic safety threats in greater detail than ever before. Traffic safety data underpins every resource allocation decision, especially when trying to examine the whole transportation system and its alignment with the Safe System Approach.

As new tools and technologies emerge, how will it change the way we collect, leverage, and integrate safety data into our planning processes? In this blog, I’ll try to answer this question and share some insights from the Association of Transportation Safety Information Professionals (ATSIP) Traffic Records Forum which I attended with my colleagues, Ryan Klitzsch and Casey Woodley.

A Short Primer on Traffic Records

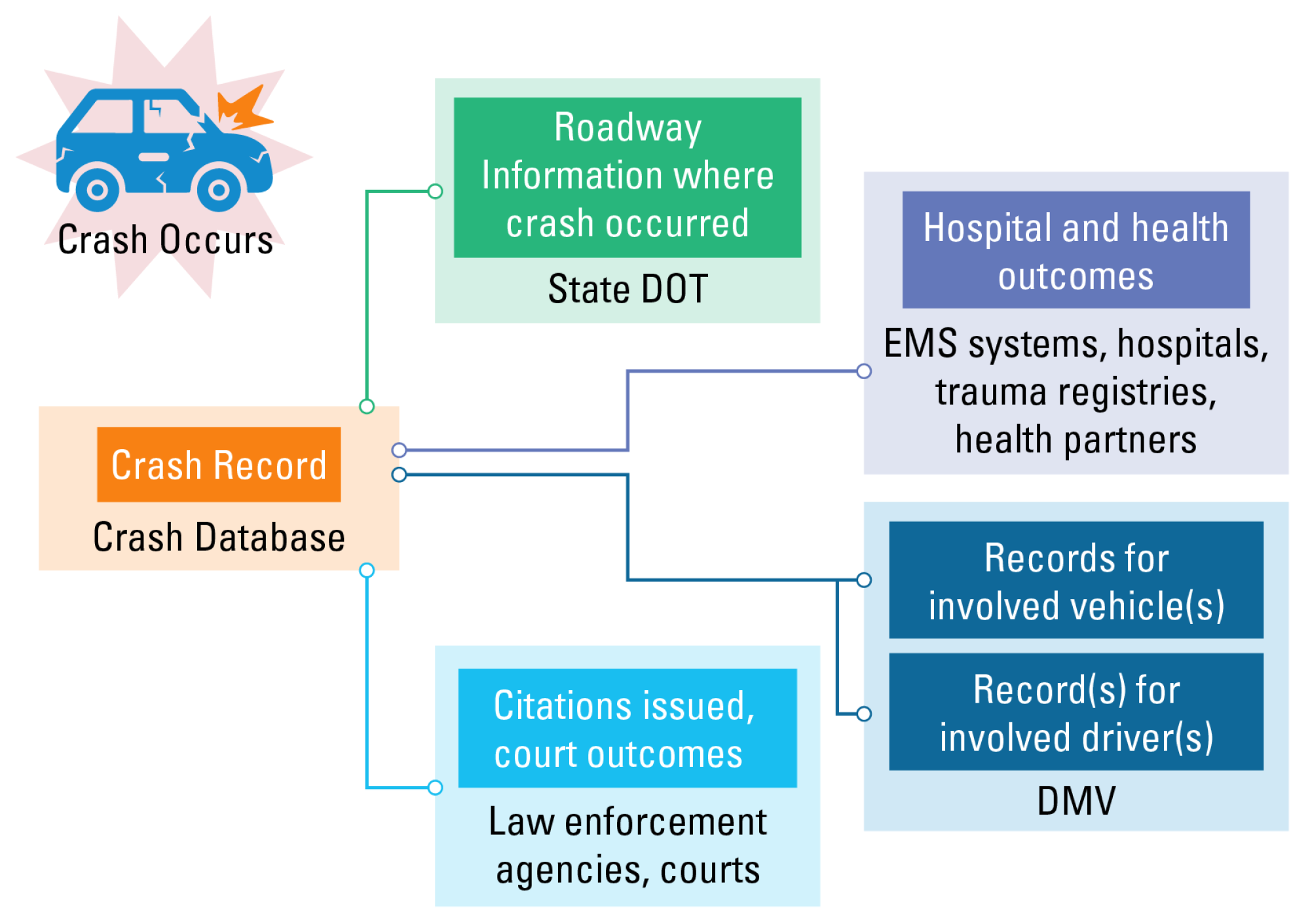

Traffic records professionals currently operate a model of six typical data system types for how safety data can come to be. This differs from state-to-state. In some states, these databases are managed by different agencies; in others, data is more centralized.

|

Data System |

State Agency Owner |

Data Relevance |

|---|---|---|

|

Crash |

Varies, often managed by state highway safety offices (SHSO) but can be state departments of transportation (DOT), state police, state departments of motor vehicles (DMV), or another agency. |

This is the database of traffic crashes, a compendium of crash reports completed by law enforcement—previously on paper forms, now mostly digital. Transportation safety professionals and the public traditionally focus on this as the most common data source for roadway safety. |

|

Driver |

State licensing agency, or DMV. |

This is every DMV’s driver history record, which also notes license status, offense history, and other valuable traffic safety data points from a driver's history. |

|

Vehicle |

State licensing agency, or DMV. |

This is every DMV’s vehicle record, which notes all vehicles' unique crash histories. |

|

Roadway |

State DOT. |

This is the state DOT’s inventory of roadway locations, geometry, and traffic control devices. |

|

Citation/Adjudication |

Law enforcement agencies and court systems. |

These are offender criminal justice records including criminal records (traffic offense tickets, arrests, charges, and investigation information) and court information (traffic cases, convictions, and terms of supervision). |

|

Injury Surveillance |

This is a grab bag of data from EMS systems, hospitals, trauma registries, rehabilitation systems, public health, vital records, and more. |

Health records document injuries and fatalities sustained in traffic crashes and sometimes can reveal unique key details such as EMS response times. |

Each traffic records database contains part of the story of every crash.

Every state has an interdisciplinary state Traffic Records Coordinating Committee (TRCC) made up of representatives from these various systems. The community is focused on improving all of these databases through six national traffic records performance measures.

|

Timeliness |

How fast data related to a crash is entered into the system and available for analysis. |

|

Accuracy |

Whether the data is free from error. |

|

Completeness |

How many missing records there are, including gaps within records. |

|

Uniformity |

How consistent the records are with data standards, often national standards. |

|

Integration |

How much a database is linked to other databases or has the ability to have separate data sources linked (see below). |

|

Accessibility |

How easily users and stakeholders can access the data to make informed decisions. |

For more details, ATSIP has recently made available its free Traffic Records 101 training.

In traffic records projects, there have been over-arching trends in the last decade and much of ATSIP discussions were focused on advances and innovative projects in these various areas:

Paper to Digital: Converting paper forms of citations and crash reports to electronic reporting, which also involves in-vehicle equipment and training for law enforcement.

MMUCC Compliance: The Model Minimum Uniform Crash Criteria (MMUCC) serves as a national model crash reporting form. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) just released v.6.0 (this author served on the committee), and several states are planning updates to their own forms. Unfortunately, some states are still working to upgrade from MMUCC v.4.0 or even earlier MMUCC versions. Outdated crash forms can hinder the ability to fully understand and address traffic safety issues.

Database Modernization: Unfortunately, IT databases are not static. State systems have to keep up with technology and functionality, and this can be expensive. Many state agencies are trying to figure out how to upgrade outdated, legacy systems. In the last year, many states applied for NHTSA’s new, massive State Electronic Data Collection (SEDC) grant program to do just this.

System Integration: Many state databases are separated from each other but the vision for the future is that all this data could be linked together on a technological level. When a crash happens, data from the crash database, DMV, state DOT, and healthcare systems would automatically be pulled together to provide a more complete view of what happened in any given crash, and all crashes overall. States have made great strides towards integration, but there is significant work to be done.

If you like these insights, join the nearly 1,700 others who subscribe to my Safe System Weekly newsletter on LinkedIn, where I bring you the top transportation safety news and insights on a weekly basis.

Traffic Records Programs Still Face Many Challenges

Traffic records modernization varies widely across the country. Many states have implemented effective, modern traffic records systems and have made great strides in data integration. However, other states are struggling to modernize. Notably, many of the same barriers to traffic records improvement from 10-15 years ago still persist today:

Lack of Funding: As traffic records have become largely electronic, program improvements have also become more expensive.

Lack of Inter-Agency Cooperation: Agencies have to agree to link databases together. However, lack of coordination and bandwidth remains a persistent challenge. Other policy issues like data privacy rules have grown as barriers.

Burden of IT Development: Unlike designing a new paper form, enhancing electronic traffic records typically requires enlisting an outside IT vendor, know-how on IT specs, extensive end-user validation of the results, and training for law enforcement officers who will have to enter the data.

Lack of Support: Other important safety issues like speeding, distracted driving, impaired driving, and others often draw more attention than traffic records, including among policymakers who make funding decisions.

We often talk about the lack of good data related to distracted driving and drug-impaired driving, but these are related to more fundamental issues. We should know a lot more about all traffic crashes than we do today. Instead, we are still forced to plan with knowingly poor or incomplete information. Many practitioners and partners at ATSIP presented cutting-edge technologies and programs. But many state data systems still have a way to go even on the basics.

When the rubber hits the road, data shortcomings can also have fatal results. You have likely heard instances of horrible crashes occurring and after the crash we discover that it was caused by an offending driver who has had multiple prior serious traffic convictions. How is this person allowed to keep driving? Unfortunately, it still happens, in part due to data about offender history that is either incomplete or not shared within or across state lines.

Innovation #1: Telematics Data Shows New Safety Insights

While traffic records programs have typically focused on legacy crash data described above, many companies have reached a level of scale in which telematics data—collected from connected vehicles, wireless devices, and other sources—can reliably provide new insights on transportation safety metrics, such as real-time crash data, incidence of harsh braking, speeding, and data about issues not well reflected on crash forms, like distracted driving. This information can be mapped and overlaid with legacy data to reveal patterns useful for safety planning. Many traffic records programs are investigating how they can leverage telematics data to supplement and fill in gaps.

Caltrans used LOCUS Safe to investigate the exposure of road users, calculate crash rates, and inform other statistical analyses for their Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) Implementation Plan and Target Setting program.

Our mobility intelligence platform, LOCUS, offers a product, LOCUS Safe, that combines your agency’s regional crash data with cellphone and connected vehicle data to help you study the number of crashes over total trips (exposure rate), isolate safety hot spots, and identify affected at-risk communities.

Innovation #2: Autonomous Vehicle Tech Improves Safety and Collects New Data

Autonomous vehicle technology not only promises to improve safety and mobility, but can also generate new, informative data. This author can list at least four types of applications for AV data. AV applications can also be considered by the way in which they potentially involve private personal information about drivers and road users.

|

Data Application |

Explanation |

Use of Personally Identifiable Information (PPI) |

|---|---|---|

|

AV safety performance |

This is already sought by state DMVs, NHTSA, and others regulating AV safety. Concerns persist about how well AVs detect some vulnerable road users like pedestrians and motorcyclists. |

Potentially includes PPI (though could be anonymized). |

|

Crashes involving AVs |

Data sought by regulators, not only to enrich individual crash reports, but also to analyze AV safety performance. |

Potentially includes PPI (though could be anonymized). |

|

Crashes near AVs |

AVs use RADAR, LIDAR, SONAR, cameras, and other sensors to collect detailed information about their surroundings, and it is only a matter of time before they record data of interest in a separate crash investigation. |

Potentially includes PPI (though could be anonymized). |

|

Aggregate population-level safety data |

This is what traffic records and highway safety professionals and researchers are probably most interested in. How can we use data collected by AVs to improve safety planning? |

Anonymized. |

In this environment where we are mulling data possibilities, ATSIP Forum audience members posed an intriguing General Session Panel on AVs and data: can automakers and tech companies cooperate to standardize the legitimate sharing of AV data? The panelists were candid. While they appreciated the spirit of the question, industry agreement on this point may be difficult. A key reason not explicitly stated is that data—even safety data—has business value; it is bought and sold, is used confidentially for competitive purposes, and can be used against the companies themselves.

The discussion also broached the ongoing debate about the safety of AVs. Companies like Waymo and others have devoted billions of dollars to develop this technology in good faith to deliver this technology as advertised: to truly provide safer mobility. Audience members discussed among themselves that while AVs and other technologies theoretically disconnect risky behaviors from driving, they don’t address underlying behaviors. If we are looking at a long-term experience in which we have a mix of autonomous and traditional vehicles on the road, there will still be a need to address many of the risks we have today that are caused by drivers themselves.

Tech does what it does, but not what it doesn’t. Another speaker presented this idea by sharing a video from eight years ago from the National Association of State EMS Officials (NASEMSO). The video offered a futuristic vision of data sharing for EMS service, with automatic crash notification, seamless data interoperability, and the linkage of health records, so that emergency responders can arrive at crash scenes informed and provide top-notch lifesaving service. All of these technologies are possible today, but the kicker is that they are rarely deployed today, eight years later. Technology solutions have achieved much in many different directions, but they haven’t solved some of the more fundamental issues, like collaboration needed between data holders.

Innovation #3: Is AI The Next Traffic Data Frontier?

It’s hard to attend any conference today without a discussion of AI, and ATSIP was no exception. Several applications were discussed to streamline many tedious traffic records tasks.

Enhancing data analysis processes

Crash diagramming

Data cleaning and validation

Data linkage

Imputation of incomplete data

Completing crash reporting paperwork for law enforcement (though defense attorneys would likely take exception!)

An important note is that quality AI outcomes depend on quality data going in. Unfortunately, all traffic datasets have at least some problems. When it comes to AI, it’s “garbage in, garbage out.” Plus, government agencies are likely to have a slow road towards using AI at scale with confidential or sensitive data.

This author reflects that many amazing consumer technologies have emerged like smart phones, entertainment options, personal computing, and more. But, when transportation technology becomes newly possible, it tends to crash into the real world again and again. Consider some examples:

|

Technology |

Benefits |

Concerns |

|---|---|---|

|

Connected vehicles |

Connectivity, mobility and safety. |

Consumer privacy. |

|

AVs/Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) |

Mobility, safety, and convenience. |

Misuse; use of automation when driver supervision is needed. |

|

Ride-hailing |

Mobility, convenience, economic independence. |

Regulatory disruption, labor/workforce issues. |

|

Automated enforcement |

Safety. |

Surveillance, privacy concerns. |

All of the concerns listed above are also posed today with AI. Like with AI, government tends to move slowly to address issues and policy questions that emerge so quickly.

What Do We Do Now?

It is hard to predict the future, but one thing we do know is that we should all be thoughtful as these technologies evolve. My colleague Sogand Karbalaieali published a blog, “How to Make the Most of New Technologies: AI & Digital Twins,” which listed some basic guideposts for AI moving forward:

When using AI, know what you’re doing it for.

Make sure technology is addressing problems at the root.

Prepare the workforce for new technology.

Identify and mitigate risks.

We know that AI, in some form, will be a part of the future of traffic records, traffic safety, and transportation overall. We’re currently thinking about how AI can help our clients solve problems, but also where it perhaps may not.

Connect With Us

For those managing traffic records programs, we offer a variety of services that can help enhance your traffic records efforts, ensure traffic records can contribute to impactful safety programs, and prepare for tomorrow: TRCC management, preparing and implementing state traffic records strategic plans, applications for traffic records grants, updating crash reporting forms, advancing electronic reporting, safety telematics market analysis, traffic records performance measurement, and more.

The Safe System Approach provides that data should be the foundation of everything we do. We agree, and we look forward to your partnership.

If you like these insights, join the nearly 1,700 others who subscribe to my Safe System Weekly newsletter on LinkedIn, where I bring you the top transportation safety news and insights on a weekly basis.